The {LSTbook} package provides software and datasets for

Lessons

in Statistical Thinking.

Version 0.6 of {LSTbook} was released on CRAN by

February 2024. Note that previous versions did not include the

take_sample() function, which is used extensively in

Lessons. The CRAN version is also published for use with webr

(as are most CRAN packages).

For more recent updates:

{LSTbook} from GitHub with:# install.packages("devtools")

devtools::install_github("dtkaplan/LSTbook")Via r-universe.dev: https://dtkaplan.r-universe.dev/LSTbook

In the YAML for a webr document, refer to the repository thus

under the webr index:

repos: ["https://dtkaplan.r-universe.dev"]

The {LSTbook} package has been developed to help

students and instructors learn and teach statistics and early data

science. {LSTbook} supports the 2024 textbook Lessons

in Statistical Thinking, but instructors may want to use

{LSTbook} even with other textbooks.

The statistics component of Lessons may fairly be called a radical innovation. As an introductory, university-level course, Lessons gives students access to important modern themes in statistics including modeling, simulation, co-variation, and causal inference. Data scientists, who use data to make genuine decisions, will get the tools they need. This includes a complete rethinking of statistical inference, starting with confidence intervals very early in the course, then gently introducing the structure of Bayesian inference. The coverage of hypothesis testing has greatly benefited from the discussions prompted by the American Statistical Association’s Statement on P-values and is approached in a way that, I hope, will be appreciated by all sides of the debate.

The data-science part of the course includes the concepts and

wrangling needed to undertake statistical investigations (not including

data cleaning). It is based, as you might expect, on the tidyverse and

{dplyr}.

Some readers may be familiar with the {mosaic} suite of

packages which provides, for many students and instructors, their first

framework for statistical computation. But there have been many R

developments since 2011 when {mosaic} was introduced. These

include pipes and the tidyverse style of referring to variables.

{mosaic} has an uneasy equilibrium with the tidyverse. In

contrast, the statistical functions in {LSTbook} fit in

with the tidyverse style and mesh well with {dplyr}

commands.

The {LSTbook} function set is highly streamlined and

internally consistent. There is a tight set of only four object types

produced by the {LSTbook} computations:

{ggplot2} compatible but much

streamlined)Vignettes provide an instructor-level tutorial introduction to

{LSTbook}. The student-facing introduction is the

Lessons in Statistical Thinking textbook.

Every instructor of introductory statistics is familiar with textbooks that devote separate chapters to each of a half-dozen basic tests: means, differences in means, proportions, differences in proportions, and simple regression. It’s been known for a century that these topics invoke the same statistical concepts. Moreover, they are merely precursors to the essential multivariable modeling techniques used in mainstream data-science tasks such as dealing with confounding.

To illustrate how {LSTbook} supports teaching such

topics in a unified and streamlined way, consider to datasets provided

by the {mosaicData} package: Galton, which

contains the original data used by Francis Galton in the 1880s to study

the heritability of genetic traits, specifically, human height; and

Whickham results from a 20-year follow-up survey to study

smoking and health.

Start by installing {LSTbook} as described above, then

loading it into the R session:

library(LSTbook)In the examples that follow, we will use the {LSTbook}

function point_plot() which handles both numerical and

categorical variables using one syntax. Here’s a graphic for looking at

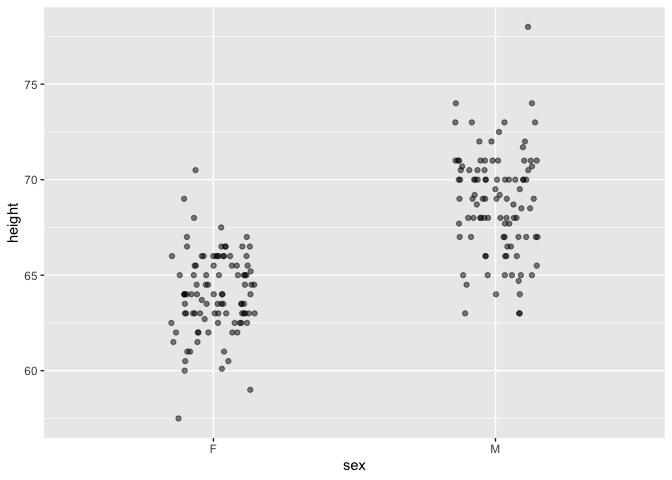

the difference between two means.

Galton |> point_plot(height ~ sex)

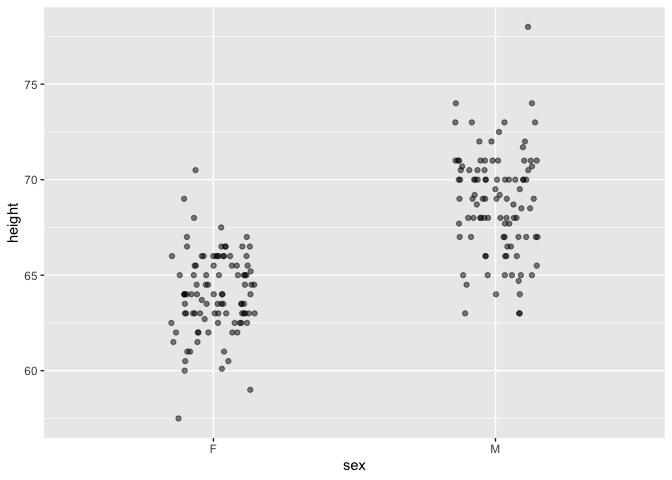

Point plots can be easily annotated with models. To illustrate the difference between the two means, add a model annotation:

Galton |> point_plot(height ~ sex, annot = "model")

Other point_plot() annotations are violin

and bw.

In Lessons, models are always graphed in the context of the underlying data and shown as confidence intervals.

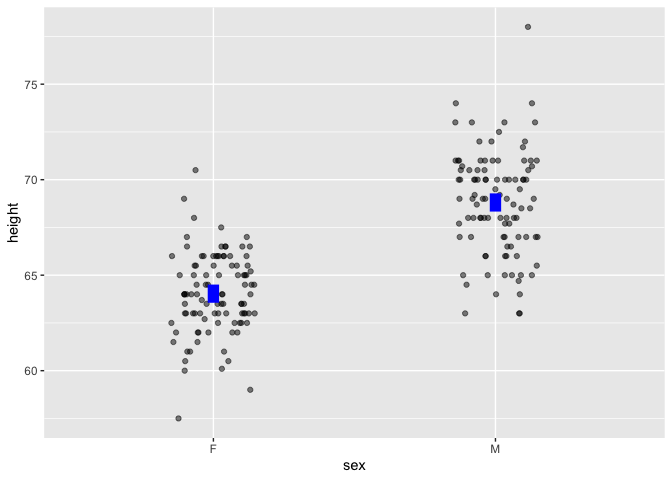

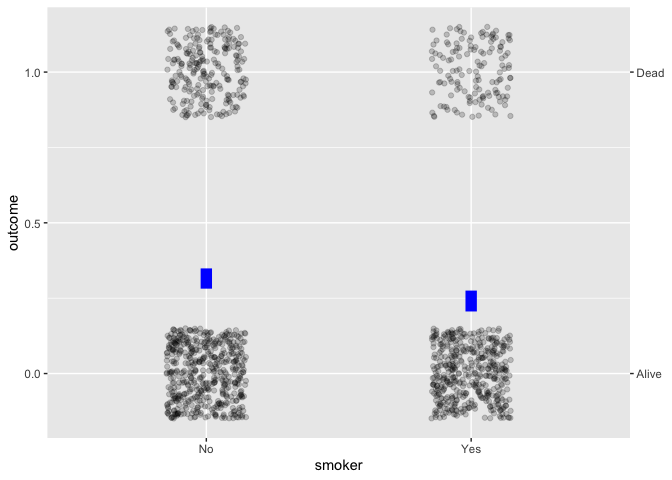

The same graphics and modeling conventions apply to categorical variables:

Whickham |> point_plot(outcome ~ smoker, annot = "model")

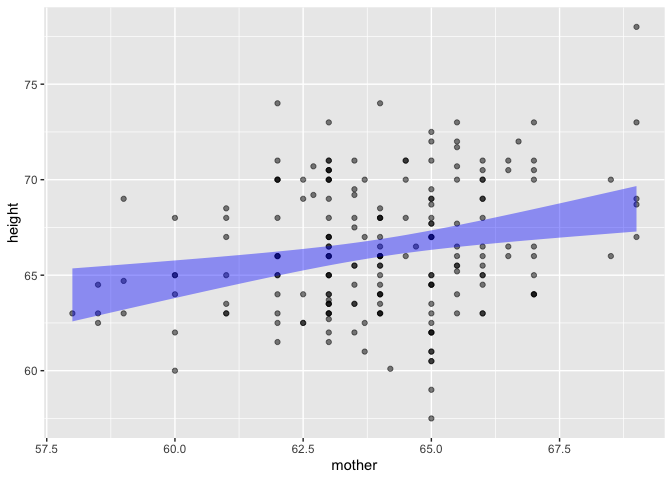

Simple regression works in the same way:

Galton |> point_plot(height ~ mother, annot = "model")

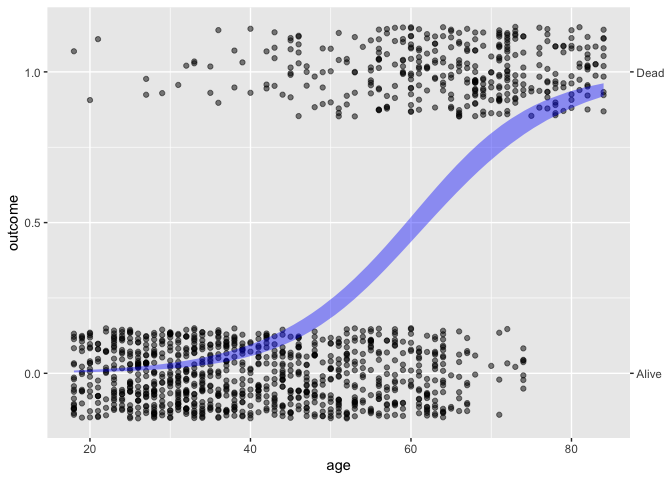

Whickham |> point_plot(outcome ~ age, annot = "model")

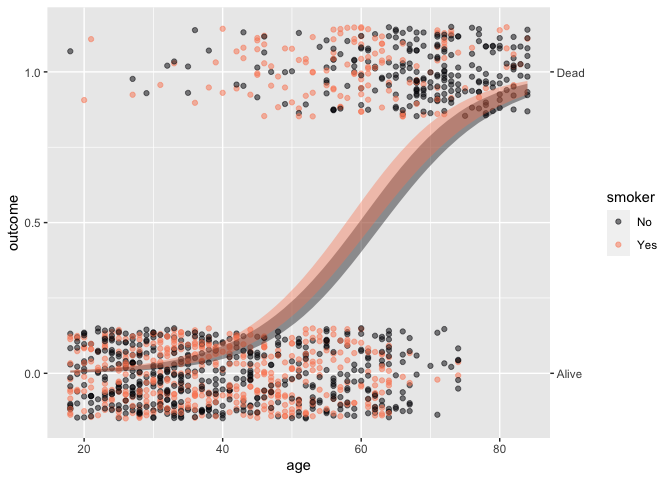

The syntax extends naturally to handle the inclusion of covariates.

For example, the simple calculation of difference between two

proportions is misleading; age, not smoking status, plays

the primary role in explaning mortality.

Whickham |> point_plot(outcome ~ age + smoker, annot = "model")

NOTE: To highlight statistical inference, we have been working with an n=200 sub-sample of Galton:

Galton <- Galton |> take_sample(n=100, .by = sex)Quantitative modeling has the same syntax, but rather than rely on

the default R reports for models, {LSTbook} offers concise

summaries.

Whickham |> model_train(outcome ~ age + smoker) |> conf_interval()

#> Waiting for profiling to be done...

#> # A tibble: 3 × 4

#> term .lwr .coef .upr

#> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 (Intercept) -8.50 -7.60 -6.77

#> 2 age 0.110 0.124 0.138

#> 3 smokerYes -0.124 0.205 0.537To help students develop an deeper appreciation of the importance of covariates, we can turn to data-generating simulations where we know the rules behind the data and can check whether modeling reveals them faithfully.

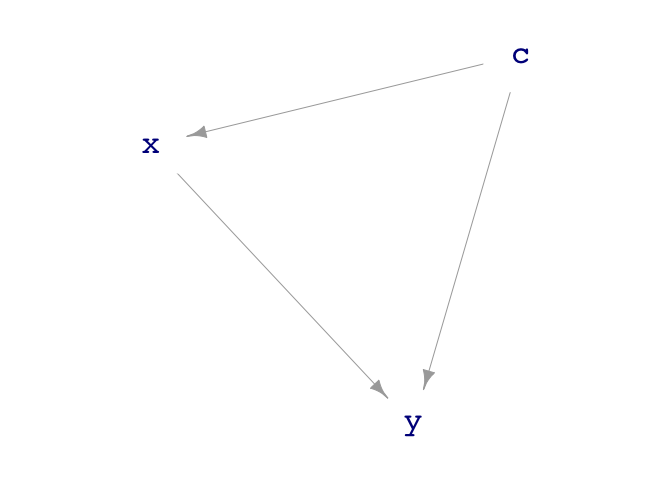

print(sim_08)

#> Simulation object

#> ------------

#> [1] c <- rnorm(n)

#> [2] x <- c + rnorm(n)

#> [3] y <- x + c + 3 + rnorm(n)

dag_draw(sim_08)

From the rules, we can see that y increases directly

with x, the coefficient being 1. A simple model gets this

wrong:

sim_08 |>

take_sample(n = 100) |>

model_train(y ~ x) |>

conf_interval()

#> # A tibble: 2 × 4

#> term .lwr .coef .upr

#> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 (Intercept) 2.75 3.01 3.27

#> 2 x 1.14 1.32 1.51I’ll leave it as an exercise to the reader to see what happens when

c is included in the model as a covariate.

Finally, an advanced example that’s used as a demonstration but

illustrates the flexibility of unifying modeling, simulation, and

wrangling. We’ll calculate the width of the x confidence

interval as a function of the sample size n and averaging

over 100 trials.

sim_08 |>

take_sample(n = sample_size) |>

model_train(y ~ x) |>

conf_interval() |>

trials(times = 2, sample_size = c(100, 400, 1600, 6400, 25600)) |>

filter(term == "x") |>

mutate(width = .upr - .lwr)

#> .trial sample_size term .lwr .coef .upr width

#> 1 1 100 x 1.372233 1.560350 1.748467 0.37623423

#> 2 2 100 x 1.332790 1.490733 1.648677 0.31588668

#> 3 1 400 x 1.421812 1.505607 1.589403 0.16759077

#> 4 2 400 x 1.499239 1.580337 1.661436 0.16219628

#> 5 1 1600 x 1.424356 1.466122 1.507888 0.08353176

#> 6 2 1600 x 1.436348 1.477919 1.519491 0.08314316

#> 7 1 6400 x 1.474246 1.494887 1.515529 0.04128310

#> 8 2 6400 x 1.487190 1.508327 1.529465 0.04227480

#> 9 1 25600 x 1.495289 1.505822 1.516355 0.02106636

#> 10 2 25600 x 1.498624 1.509280 1.519937 0.02131267I’ve used only two trials to show the output of

trials(), but increase it to, say, times = 100

and finish off the wrangling with the {dplyr} function

summarize(mean(width), .by = sample_size).

#> sample_size mean(width)

#> 1 100 0.34800368

#> 2 400 0.17059320

#> 3 1600 0.08483481

#> 4 6400 0.04251015

#> 5 25600 0.02123563